|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

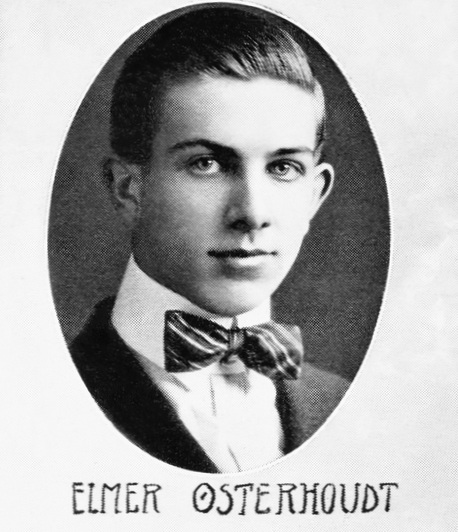

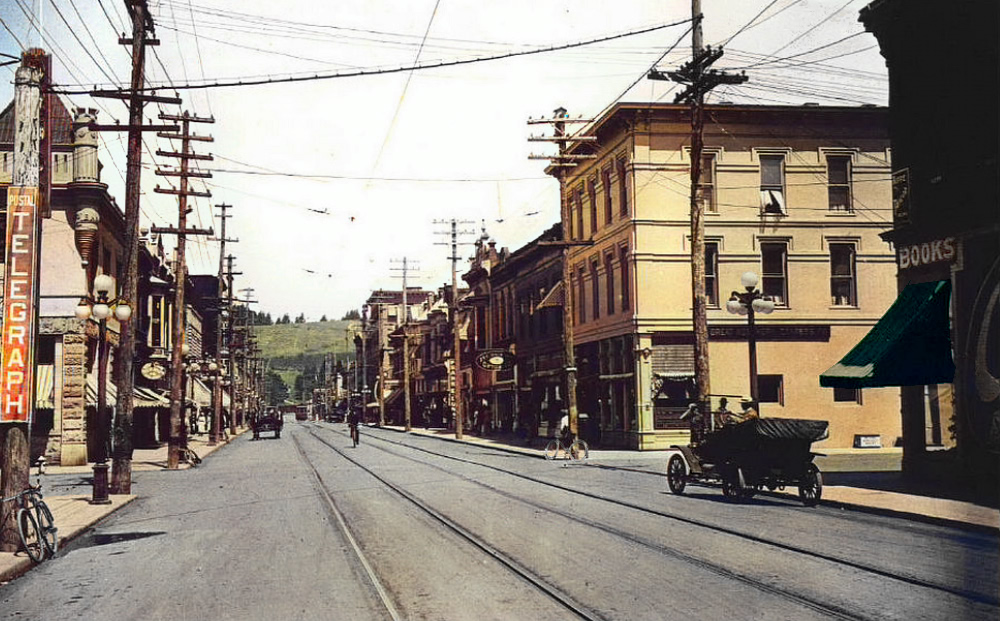

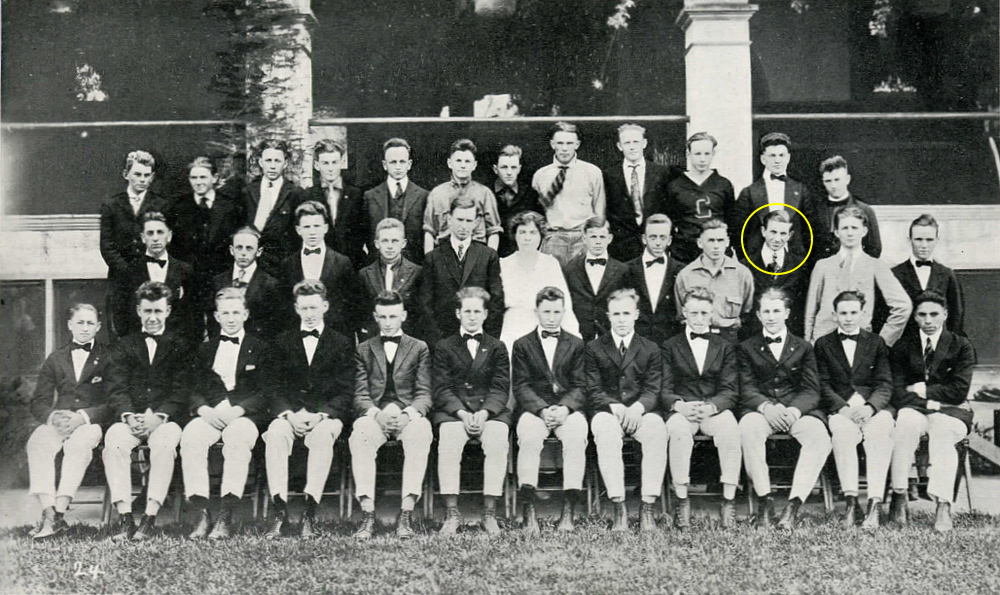

Photo from 1918 Compton Union

High School yearbook |

Photo thanks to Victor Rodriguez |

|

|

|

One day in 1915,

after reading a 10¢ booklet*

concerning a new technology called "wireless telegraphy," a 16

year old boy named Elmer G. Osterhoudt began the

construction of a crystal radio. He was attempting to

receive the signals that were said to be invisibly traveling

through space, undetectable by human senses.

He wound a beautiful coil made of 200 turns of 28 gauge

cotton covered wire on a piece of broom handle. Then he

painted it with white lead paint which he had invented

himself. Connecting the coil to a galena crystal, headphones

and antenna, he listened in vain for the wireless signals.

He soon came to the realization that his radio didn't work.

The lead in the paint had ruined the coil. The radio was

stone dead; he couldn't get as much as a click out of the

headphones.

Elmer had a neighbor who was also interested in Wireless and

who was also named Elmer.**

This Elmer also had made a radio that didn't work. He came

by with his radio because Elmer Osterhoudt "knew all about

radio." Elmer put the other Elmer's non-painted coil into

his set and in came a powerful rotary spark signal from

station 6JG! ***

The magic of this single event influenced the entire

remainder of his life. A first-hand account can be found on

Page 2 of "How To Make Coils" by Elmer Osterhoudt, written

in 1957.

Link

* In HB-5 "CRYSTAL SET

CONSTRUCTION" Elmer names two magazines, "QST" and "The

Electrical Experimenter." In April of 1915 the price of

"The Electrical Experimenter" went from 5¢ to 10¢, which narrows down the volume

that Elmer actually read. The May edition contains several

plans for home made crystal detector stands, and some

articles on antennas and other wireless related subjects. The July issue, on page 109, shows

a simple wireless receiving set. There is no coil data, but

the illustration resembles what Elmer described above. Page

109 also has an article on how to blow up a toy boat using

homemade wireless apparatus and a simple mine filled with

gun powder.

Link

QST was also 10¢

but there were no "how to" articles published in QST at the

time. In any case, it doesn't seem that Elmer put down the

magazine and spontaneously assembled a crystal set. He

already had the wire, the detector, some sort of antenna, and a pair of

headphones.

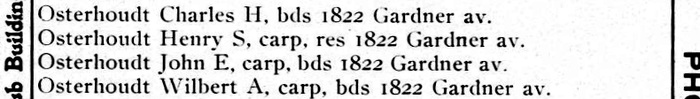

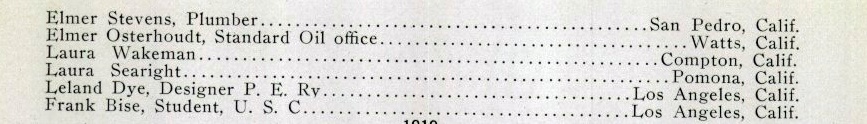

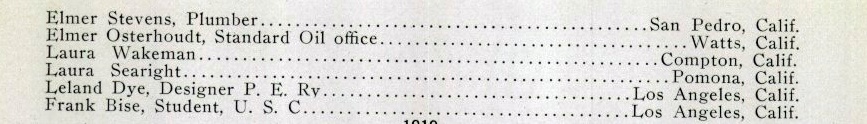

**

After searching Los Angeles property records and the US

census for any neighboring household that had a boy named

Elmer of the appropriate age, fellow MRL fan Victor

Rodriguez has determined that this person is Elmer Stevens.

He appears in the Compton Union High School yearbook with

Elmer Osterhoudt.

Link

The two Elmer's were in the high school band

and school orchestra together, but their friendship is

unknown. Elmer referred to him as "a neighbor boy" in his

account.

*** There was indeed an amateur with the call

sign 6JG. The 1916 edition of "Radio Stations of the United

States," issued by the Department of Commerce, lists him as

James A. Homand of 1423 McKinley Street in Los Angeles,

California. This address is about three miles from where

Elmer lived. |

|

|

|

|

|

In 1917 Elmer Osterhoudt and his family

lived at this address at 1936 East 77th Street in Los

Angeles, CA. The 100+ year old house, built in 1908, lies

under the additions and modern exterior of this building.

Elmer obtained

the amateur call sign 6NW in 1917. Prior to that he used the

made-up call of "EO." While living at 77th and Crockett (the house

in the photo above), he had erected a 55 foot antenna mast

made of all sorts of 2x4s, 2x3s and pairs of 1x2s. It had a

dozen guy wires made of bailing wire. On top of the mast was

a four wire antenna, each wire separated by 30 inches. (He

didn't say what the other end was connected to.) It was up

for about a year when his father decided to move, so he had

to take it down. That's when he noticed the bailing wire had

almost rusted through. It would have fallen down by itself

in another month, and would have either hit the house or

have fallen into the street!

If that was the case, we're probably looking at the exact

spot where the mast was located.

It was just as well. On April 6, 1917, due to the war, it

became illegal for a private citizen to own a working

transmitter or receiver. It was considered an act of treason

to operate a transmitter, and no excuse would be made if

they were operated by "boys." In addition, the Department of

Commerce directed that "the antennae and all aerial wires be

lowered to the ground." It's almost hilarious that Elmer's

antenna would have complied of its own accord.

On May 1, 1917, the Osterhoudt's moved to 241 E. Truslow

Avenue in Fullerton, California. Elmer was interested in

entomology and biology, and without being able to use his

radio equipment he pursued these fields instead. He was a

member of the Lorquin Natural History Club, he corresponded

with professional entomologists, and placed ads in the

Lepidoptera, a Boston publication, to trade insects and

butterflies from the east coast. He raised the

butterflies himself.

By 1918 the

Osterhoudt's were back in Los Angeles at the same

address of 1936 E. 77th Street, but would eventually move to 8011 Crockett

Boulevard, a few blocks away.

This might have been the end of the story of Elmer

Osterhoudt's interest in radio, just another boyhood hobby

set aside. However, the young Elmer was resourceful.

Since it was illegal for a civilian to own radio apparatus,

he joined the Navy and became a Radio Mechanic! He was in

good company. Nearly 80% of the Radio Amateurs in the U.S.

joined the Armed Forces. Of the 4000 radio men, 1000 of them

had enlisted in the Navy.

|

|

|

|

| Elmer may have

read this article in the July 1917 issue of QST. This issue

specified it was the Navy who needed wireless operators, and posted the pay rates for radio electricians, from $41

dollars a month for Third Class to $61 dollars a month for

First Class. It stated that Uncle Sam expected every

wireless operator to do his duty and enlist. A free cot, food, and a uniform were included,

of course. |

|

|

|

|

During his lifetime Elmer Osterhoudt would (in all

probability) hand-wind more coils and design and sell more

crystal radios than anyone who has ever lived. He outlasted

all his competitors in the mail order crystal radio

business. He, along with his wife Mabel, ran a mail order

company named "Modern Radio Laboratories" for 55

years.

He sold thousands of kits, coils, crystals and all parts

related to crystal radios, many of which he made himself. He

published the MRL catalog, the MRL "Radio Flyer," MRL handbooks,

MRL "Detail

Prints" and a quarterly publication called "Radio Builder

and Hobbyist." He printed them himself, at first with a

mimeograph machine and later on a lithograph printer.

Everything needed for a radio could be found in his catalog;

coils, capacitors, headphones, switches, jacks, binding

posts, sockets, crystal stands, knobs, batteries, wire, all

sorts of hardware and even vacuum tubes and transistors. He

manufactured over FIFTY-FIVE types of coils, all made by

hand!

|

|

|

|

|

The MRL logo was hand drawn by Elmer, and almost

every one is different. "First use in commerce" of Elmer's

trademarks is listed as December 15, 1932. Today, these

trademarks are owned by Paul Luther Nelson, current owner of Modern

Radio Laboratories®, who registered the

logos to himself in 1999. |

|

|

|

|

There is little

information about Elmer available but we can glean some

details from city directories, census records, birth and

death certificates, advertisements, and his literature - and

he wrote a lot of literature. He also included a hand

written note with each order, some of which have survived.

His company, Modern Radio Laboratories, was

established in 1932. It says so, right at the top of the

"EXPERIMENTER'S CATALOG." Oddly enough, Elmer rarely used

the entire name in his handbooks and other publications. On the catalog it is shortened to "MODERN RADIO LABS" and

elsewhere simply to "MRL." Some of his magazine

advertisements listed the company as "Modern Radiolabs" but

later it was shortened to "Laboratories," since these ads

were charged by the number of words.

Every one of his handbooks has this list of accomplishments

printed inside the front cover: |

|

"WITH RADIO SINCE 1915." including:

RADIO Operator, R.C.A. Marine Service.

Radio Mechanic, Maximum, USN.

Technician, Electrical Products Corporation.

Southern California Edison Company.

Majestic Electrical Products.

U.S. Motor Company

Manchester Radio Electric Shop

Modern Radio Laboratories

Amateur and Radio Service

6NW (1919)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Scotts Mills, Oregon. Photo taken in 1912 by

James Eaton.

(Click for full size - will open in

new tab.)

|

|

|

|

Elmer was born in the Scotts Mills Precinct of

Oregon on October 6, 1899, the son of Wilbert and

Minnie Osterhoudt. Wilbert (also known as William)

was a farmer, carpenter, and a cabinet and furniture

maker.

According to the 1900 census, the family lived on the farm of Charles Higby

Osterhoudt, Wilbert's father. Wilbert's mother Elizabeth

(maiden name Woodruff), had passed away in 1896 at

the age of 64. Also on the farm were

two of Wilbert's brothers, Henry and John. Cyril

Wilbert Osterhoudt, Elmer's brother, was born on

April 17, 1901.

Note: Elmer's

1942 draft card states that he was born in Butte Creek,

Oregon. Butte Creek was incorporated into Scotts

Mills in 1916, but Elmer was apparently born on his

grandfather's farm and not in the town itself. A mortgage document from June 7, 1887

states this farm is where the actual Butte Creek

intersects the "county road leading to Silverton."

The county road is today route 213, also known as

Cascade Highway. The property line ran down the the

road and

followed Butte Creek for a short distance, and is about

two miles north-west of

Scotts Mills. Adjoining the southern end of the

Osterhoudt farm was a farm owned by Cornelius

Woodruff, Elizabeth Osterhoudt's father, and

Elmer's great grandfather. Also, 10 acres of the

Osterhoudt farm were owned by Elizabeth's sister,

Sarah Coffin. A 1929 map of the Butte Creek area

shows a plot of the Osterhoudt farm still owned by

Elmer's aunt, Luella Dicken. (See

this.)

The population of Scotts Mills at the time was about

100. There is no birth certificate for Elmer, as

none was needed in 1899. Cyril obtained a "delayed"

birth certificate in 1942. It states that he was

born in Silverton, Marion, Oregon, about 5 miles

from Scotts Mills. In fact, the current address

of the farm location is Silverton, Oregon, though it

is closer to Scotts Mills. From this we my surmise that

Cyril was also born on the Osterhoudt farm. Charles, Elizabeth and Minnie are

buried in Miller Cemetery, which sits almost exactly

between Silverton and Scotts Mills. Today, most of the

area is still open farmland.

Sometime around 1902, Charles

Osterhoudt, Wilbert, Minnie, Elmer, John and Henry

left the farm and moved

to Spokane, Washington. Cyril was probably with

them but ended up living with Wilbert's sister Nellie McConnell and her

husband Charles. The McConnell farm was

right outside of Scotts Mills.

|

Entry

from the 1903 Spokane, Washington City Directory. The house

in the listing, built in 1889, still exists. |

From Spokane

they moved to Yakama City. Charles died there in

April of 1903. Minnie Osterhoudt died of typhoid

fever in September 1903 at the age of 27. A lone

newspaper article hints that Elmer and Cyril had a

three month old brother named Clarence who died two

weeks after their mother died (see page 12). Wilbert, Henry, John,

and four year old Elmer moved to

Vancouver,

Washington. From there they moved to Eugene,

Oregon. (It may have been around this time that Cyril

was sent to live with the

McConnell's. All we have to go on is the 1910 census.)

On July 27, 1904, John

Osterhoudt married a girl named Lillie S. Shields in

Vancouver Washington. They lived on a 160 acre

homestead near Enterprise,

Oregon. John

listed himself as a farmer in the 1910 census.

Elmer wrote in MRL Data Sheets Vol. 6 that

his father owned a planing mill in Eugene. (A

planing mill takes boards from a saw mill and turns

them into finished lumber.) Actually, Wilbert didn't

own the mill outright, he had a partner named Jim

Smith. The company name was "J H Smith & Co,"

according to the city directory. The mill was

a few blocks from the

Willamette River near Skinners Butte, where the mill

race met Eighth Avenue.

Henry Osterhoudt also worked at the mill.

The 1910 census shows that Wilbert and Elmer lived

at

205 8th Avenue in Eugene. This was the actual

address of the planing mill, named "Eighth Avenue Planing Mill."

The mill was also known as "Eighth Street Planing Mill."

Wilbert's brother Henry, his wife Fanny and

their son Darrel rented a house a few blocks away

at 316 East

15th Street.

In 1912, John, Lillie and their children moved from Enterprise to

593 8th Avenue in Eugene. John then worked at the

mill, along with Wilbert and Henry.

|

|

Entry from

the 1911 Eugene City Directory.

Henry has moved from East 15th Street to

West 10th Street. The street names change

from

East to West at Willamette Street, and the

new address places his residence much closer

to the mill. |

|

Cyril was

reunited with his father and Elmer sometime between

1910 and 1912.

An article in

the Eugene Guardian states that Wilbert had

married Lela May Smith in 1911, and the 1914 City

Directory shows they lived at 656 E. 8th Avenue.

However, it seems Wilbert was abusive, and he

encouraged both Elmer and Cyril to act unkindly

towards her. Lela May went into hiding and filed for divorce in June of 1914.

The

divorce was granted on August 18, 1914.

|

Entry

from the 1914 Eugene City Directory. |

|

|

Was Lela May Smith the daughter of

James H. Smith, Wilbert's partner? After some

investigating, it has been determined she was not. There was a Lela May

Smith in Eugene who was the daughter of James Smith, but it

was a different James Smith. He was James L. Smith, a farmer who

died in 1907. This other Lela May

Smith married Clark H. Hileman in 1903 and was still married

to him when she died in 1933.

Lela May Smith Osterhoudt's mother's name was Nancy.

The 1920 census states that James H. Smith, 67, of 205 8th

Street in Eugene City, was married to Jessie D. Smith, 48

(not Nancy). His occupation was "Carpenter in a planing

mill." |

|

|

Wilbert

Osterhoudt and Jim Smith at the Eighth

Avenue Planing Mill 1909.

Click for full size.

Construction of the mill began on October

10, 1908 and it opened a month later. |

|

|

|

|

| Left to

right: Jim Smith, Wilbert Osterhoudt, Mr.

Basinette, Henry Osterhoudt, John Edwin

Osterhoudt. Click for

full size. |

|

Fun facts:

Wilbert was 5'8" tall. Henry was 5'9" and

John was 5'8". (Information from a

census document from Marion County, Oregon,

1895) When this picture was taken Wilbert

was 39 years old, Henry was 44 and John was

34. |

|

| |

The 1910 census shows

that Henry Osterhoudt, his wife Fannie (or

Fanny) and his son Darrel lived at 316 East

15th Street in Eugene.

Darrel was born in

1903 in Cottage Grove, Oregon, about 21

miles south of Eugene. He would

have been a few years younger than Elmer and

Cyril. This is interesting because the 1903

Spokane, Washington city

directory shows Henry Osterhoudt was in

Spokane with his father and brothers that year. 1903 was also the year

that their father Charles and Elmer's

mother Minnie died in Yakama City.

Fanny's maiden name was Woodruff. Henry and

Fanny were distantly related before they

were married. Wilbert, John and Henry's mother's maiden name

was Betsy Woodruff. Henry's grandfather on his

mother's side, Cornelius

Woodruff, and Fanny's grandfather Brock

Woodruff were brothers. Henry and Fanny

both had the same great grandfather, Asa

Woodruff.

The only other information we

have about Henry is that he died in 1920 at

the age of 56. At that time he

was a farmer who owned a farm in Hopewell,

Oregon, about 90 miles from Eugene but only

about 20 miles from Scotts Mills.

In 1922 Fanny moved to Portland with

Darrel, who graduated Benson Polytechnic

High School in 1924. Sometime after 1927

Darrel bought a tiny house at 3381 S.

Francis Street, and he and Fanny lived in it

for the rest of their lives. A voter

registration card shows that Hazel May

Osterhoudt, daughter of John and Lillie,

lived with them in 1936. Hazel

married Eldee Buhite in 1939 and they moved

to Washington County, outside of Portland.

(Their son, Edwin John Buhite, was a member

of The Cat Whisker Society in 1990

and mentioned his cousin Elmer Osterhoudt in

one of their newsletters.) Also living

at the Francis Street address in the 1940s was Hazel's

brother, Merrill Osterhoudt. Merrill

joined the Navy and spent 20 months in the

Pacific during WWII.

Fanny died in December of 1967 at the age of

92. Darrel died 11 months later at the age

of 65. He was a foreman working for the

Portland City Parks Department and had just

retired that June. He had been there since

1932, the year Elmer Osterhoudt created

Modern Radio Laboratories.

Henry, Fanny and Darrel are all buried in

Hopewell Cemetery. Each has the same type of

tombstone, and they are

lined up in a row.

Hopewell is located where two roads

intersect in an area of ranches, farms and a

winery. It has two churches, a cemetery, a

little store that sells coffee, and a sign

that says, "Thank You For Visiting Hopewell."

It's

considered an "unincorporated community"

and there are very few houses in the area.

Who would have been there in 1967 and 1968

to bring Fanny and Darrel back from Portland to be buried next to Henry

Osterhoudt? Who in Hopewell would even

remember them? If Fanny and Darrel lived in

Portland for 45 years or so, why aren't they

buried in Portland?

I can offer a theory: Fanny had in her will

that she wanted to be buried next to Henry.

Darrel would have taken care of this if he

was able. Then Darrel died, and since he had

no wife or children it may have been Elmer's

cousins, the children of John and Lilly, who

laid him to rest with his parents. Some of

them, including Hazel May, still lived in Oregon and Raymond

Osterhoudt lived in Portland. |

| |

|

| |

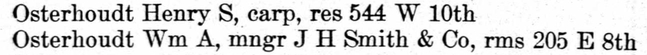

In 1912, when Elmer was 13 years old and living in

Eugene, he traded in three empty beer bottles for

the deposit and bought a 10¢ book named "The Star

Toymaker." Using the plans from this book, Elmer and

Cyril built a tin talking machine, bird houses,

motors, waterwheels, stilts, telegraph sounders,

electric bells and dry cells.

|

|

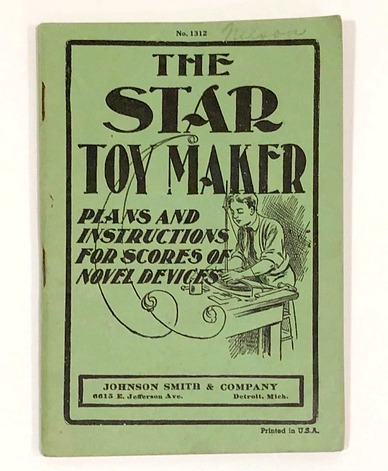

8th and Willamette Street in 1915, a few

blocks from the mill. In the background is

Skinner Butte. On the right is a

bookstore. It was probably the closest

bookstore to the mill and it's possible Elmer purchased

The Star Toymaker there in 1912. It seems he also

purchased Popular Mechanics.

(Colorized B&W photo.)

|

Early Model T Fords used dry cells to power the

ignition system. Elmer and Cyril would go to garages

and acquire the discarded dry cells to power their projects. At one time they had

about 100 of them connected together in series for

"a sparking good time." When the cells became

depleted they figured out how to chemically

rejuvenate them using a saturated solution of Sal

Ammoniac.

They used the dry cells to set off their cannon,

which was made of a foot long pipe 1" in diameter,

mounted on a 2" x 6" board. One end was closed off

with a big bolt and had a slot sawed into it to hold

the end of a lamp cord. They charged it with Potash

and Sulfur and sent an electric current through the

lamp cord. According to Elmer, they once stuck the

handle from an old umbrella into it, and it was

blown out with enough force to drive it through a

wooden box.

Handbook 8, Radio Kinks and Quips, contains

the following three sentences: "At home, my brother

and I used to drive our poor Dad nuts. We had an

Edison Cylinder record phonograph. We used to

reverse the belt and run it backwards."

Accounts of how to make a cannon out of a 1" gas

pipe, how to rejuvenate dry cells with Sal Ammoniac,

how to reverse the belt on an Edison phonograph, and

even how to acquire depleted batteries from

automobile garages can be found in Popular

Mechanics magazines that were published prior to

1912, so it seems Elmer was reading

Popular Mechanics in addition to The Star Toy

Maker.

According to Elmer, they sometimes threw their old

dry cells out their 2nd story window at their dogs

below when the dogs were "celebrating." What is

interesting about this sentence is that the

Osterhoudt's had dogs at the mill. Elmer and Cyril built "grass

sleds" and used them to sled down Skinners Butte,

which rises 250 feet above the surrounding city.

Skinners Butte is still a recreation spot today.

Near the base of the Butte was a mill race

connecting to the Willamette River. The mill race

crossed 8th Avenue at the location of Wilbert

Osterhoudt's mill at 205 8th Avenue. (There were several planing mills

at the time in the immediate area.) Skinners

Butte was only a few blocks away from the mill. On top of the

butte were the charred ruins of an observatory

which had been dynamited in 1905, so it must have

been a great place for kids to explore. Also on the

butte were two reservoirs, the larger one holding 2

million gallons of water for use by the fire

department.

|

|

The observatory atop Skinner Butte before it was dynamited.

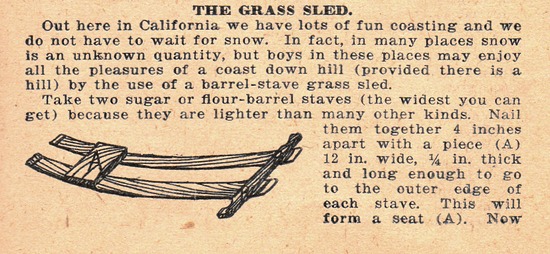

A grass sled from The Star Toy

Maker. Elmer

and Cyril would have had plenty of scrap wood

from the planing mill.

A copy of the book is on Page 13.

By the way, Elmer

still had the book in 1966.

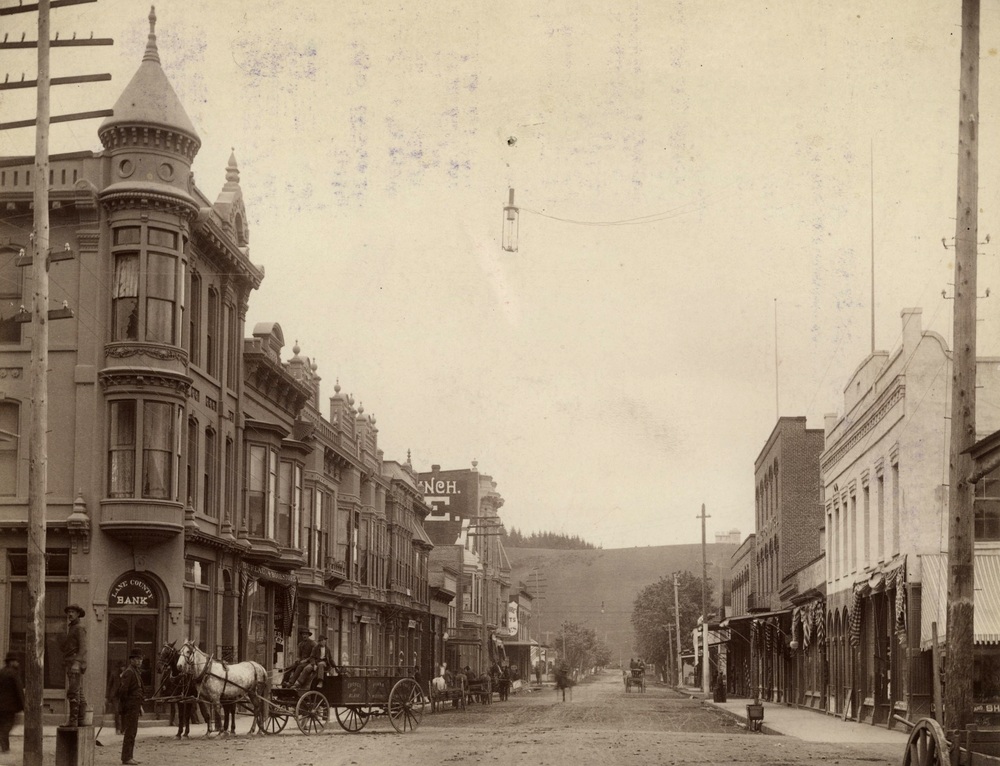

Downtown

Eugene, Oregon in 1903. Skinners Butte rises in the

background. On top of the butte can be seen the

observatory. Elmer and Cyril probably walked down

this very street. None of these buildings are still

standing as they've been replaced with modern

structures. The mill race has been filled in. The

current address of the planing mill site is 8th and

Mill Streets, which is currently occupied by the

Wayne Lyman Morse United States Courthouse.

Eugene was home to the University of Oregon. See

this

map.

The Osterhoudt planing mill is at the bottom of

Plate 16 of the 1912 Sanborn Fire Insurance maps.

Link

Plate 16 can also be viewed

here.

On August 14, 1915, one year after his divorce from

Lela May, Elmer's father married Alice Elsie

Shields, the sister of his brother John's wife,

Lillie. By this time Wilbert and Alice had a

daughter named Wilda Frances Osterhoudt. Lela May

had asked for 1/3 of Wilbert's property and $25 a

month alimony during the divorce. The Lane County

History Museum states that the J. H. Smith & Co mill

stopped operating in 1914, the year the Osterhoudt's

were divorced. It's impossible to know the exact

chain of events, but Wilbert and Alice left Eugene,

taking Elmer, Cyril and Wilda with them. They were

married in Santa Ana California, and would spend the

rest of their lives in Los Angeles.

Elmer and Cyril eventually had six half-brothers and

sisters, though two sisters died young; Nora died of

Whooping Cough when she was almost 4 years old, and

Ada May died of pneumonia the day before her second

birthday. (See Page 12 for a list of siblings.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

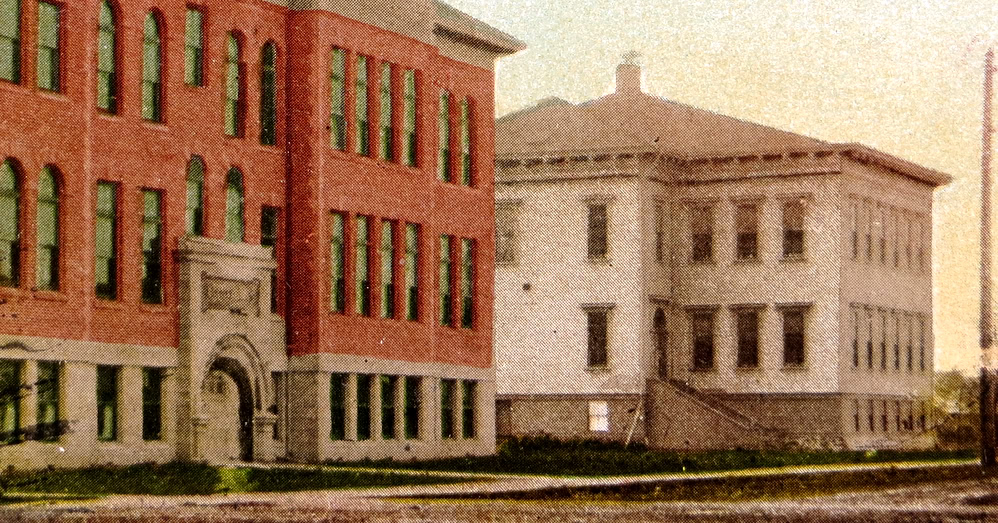

Eugene Central Grade School (on the right as it looked in

1903) where Elmer attended grade school. According

to The Eugene Daily Guard, Elmer was one of a

handful of students who successfully

completed the eighth grade examinations in the

subjects of physiology and geography while still in

seventh grade. |

|

|

Click for full sized

postcard. |

|

|

|

|

|

Eugene High School as it appeared in 1912. Built in 1900, Elmer

attended school here. If you compare this view with

the one above you'll notice an addition has been

built on the right. It was located at Willamette

Street and West 11th Avenue, a few blocks from the

mill on 8th Street. In 1915 a new high

school was built and this building became Eugene

City Hall. Elmer didn't get a chance to attend the new

school. By the time it opened, the family was in

Santa Anna or Long Beach, California.

Today a branch of Chase Bank and a

convenience store are located on the sites of the

two schools. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Willamette Street and West 11th Avenue,

120 years later. Only the fire hydrant remains, and it's

probably not even the same hydrant. |

|

|

|

|

|

1914 Freshman class at Eugene High School.

Photo from the yearbook. Click for original. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

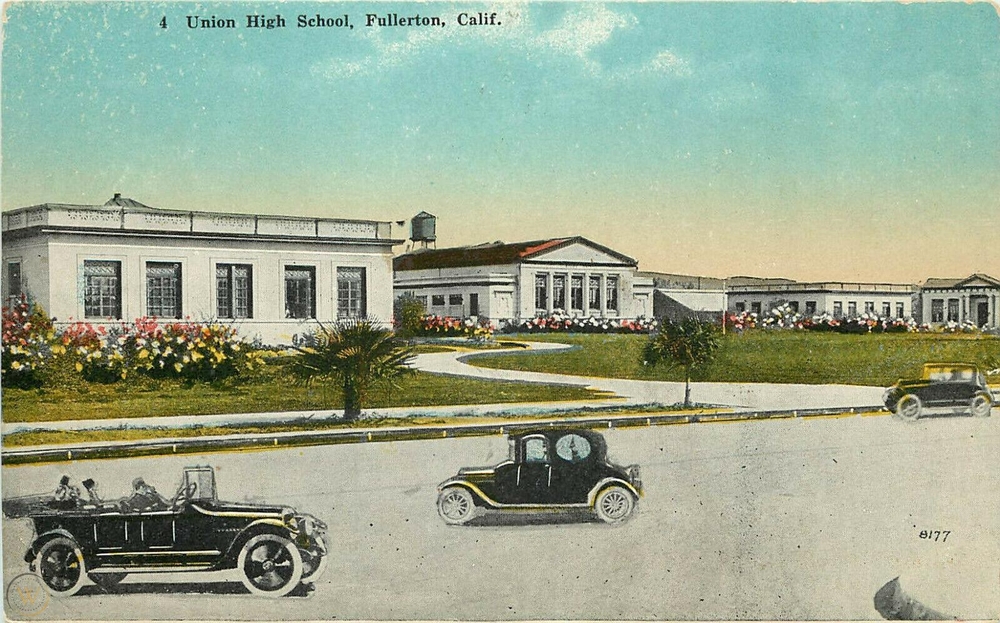

Fullerton Union High School |

|

|

In 1917 the Osterhoudt's moved from Los Angeles to 241 East Truslow Avenue in

Fullerton, California. Elmer attended Fullerton Union High

School. He took biology, was interested in

entomology, and had a large collection of insects.

In a letter to the noted entomologist Fordyce Grinnel Jr, dated May 21, 1917, Elmer wrote, "On

account of having to take my wireless down when we

were at Florence* I have gone into Entomology about

as deeply as ever again." The Junior College was in

the same building as the high school, and he

befriended the teacher who taught entomology there,

Hiram Tracy. Elmer would offer advice and

encouragement to the college students in the class.

He stated they always got plenty of specimens but

did a poor job of mounting them.

* What did Elmer

mean by "when we were at Florence?" The area where

the Osterhoudt's lived at 1936 E 77th Avenue is just

outside of the Los Angeles city limits and is known as

"Florence" or "Florence-Graham." |

|

|

|

|

|

| Of the twenty

members allowed in the Lorquin Natural History Club

in 1916, Elmer was number 14. Though the membership

was limited to twenty, there were many "Associate

Members." The club was organized in 1913 by Fordyce

Grinnell Jr. and meetings were held on the first

Friday of every month. In 1917 the name was changed

to the Lorquin Entomological Club. It is

still active today as the Lorquin Entomological

Society.

LINK |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Compton Union High School. Photo taken in 1903. The school

was six miles from the Osterhoudt residence.

|

| The

Osterhoudt's moved from Fullerton back to 1936 E. 77th Street in Los Angeles. Elmer

graduated from Compton Union High School in June of

1918. About 12% of the US population had a high

school diploma in 1918. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Compton Union High School class of 1918. |

|

|

|

|

|

Elmer Osterhoudt. |

|

|

|

|

|

Elmer

played "First Trombone" in the school orchestra and

the band. (First Trombone is the lead trombonist, requiring a strong player who can handle

high notes and intricate passages.) Also in the orchestra was Elmer Stevens

(right), who played drums.

We believe Elmer Stevens was the "neighbor boy" who

brought his non-working crystal set to Elmer

Osterhoudt in 1915.

|

|

|

-- Click on the photos above for the complete orchestra

or band group photo. -- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Los Angeles 1916 Long Beach City directory lists

W A Osterhoudt as a woodworker at Jones Sash

and Door Company, located at 1101 West Broadway. The

"W A" would be William Arthur. Unfortunately it

doesn't list his address, but the 1915 directory

lists an Alice Shields at 922 W. 6th Street, not far

from the Jones Sash & Door address. Neither of these

addresses exist today, and we don't know if the

listing is the correct Alice Shields, since her name

would have changed to Osterhoudt in August of 1915.

MRL Mystery: The Osterhoudt's lived at 657 8th Ave in

Eugene, Oregon. After they left for California a woman named Olga Jones lived at

that address, while Wilbert worked for the Jones Sash and Door Company in Long

Beach. Is this just a coincidence due to a common name, or did Olga have some

family connection with Jones Sash and Door Company?

In the preface in his handbooks, Elmer wrote that he

was a technician at "Electrical Products Company."

This was a company in Long Beach founded in 1912

that made electric and neon signs. Elmer wrote that

he worked there during the war, so this would have

been sometime after 1915 but before he was in the

Navy in 1918. Since the Osterhoudt's had moved to

77th Street by 1917, it was probably in 1915 or

1916.

| Entry from the 1913

Los Angeles City Directory. This address

is in the Long Beach area. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In 1918, Elmer worked as a laborer at Southern Board

and Paper Mills, now known as PABCO, located at

Vernon and Santa Fe Avenues in LA. (He wrote this

himself on his draft card.) The building in the

photo above was built in 1912 and would have been

quite new when Elmer was employed there. The actual

address is 4460 Pacific Blvd. The area was known as

Vernon at the time, but is now Los Angeles. 100

years later the building is still there making paper

products.

Presently, this

building is one corner of a huge complex of

buildings, some of them very dilapidated. |

|

|

On September 12, 1918 there was a U.S. Military

draft registration (the 3rd one of the war) for men

aged 18 through 45. Prior to this third draft, the

minimum age was 21. Elmer would have fallen into the

new category. Apparently, working at PABCO didn't

suit him, because he registered on the very day the

new draft went into effect, Sept 12, 1918. He and

his brother Cyril registered at the same time, but

the Navy didn't accept Cyril till August 8, 1919. It

seems Elmer was immediately accepted, as the US

military was in desperate need of radio technicians

but had no time to train them. He was stationed at

the Alameda U.S. Naval Base. The war was over "at

the 11th hour on the 11th day of the 11th month of

1918."

Draft Card

According to Elmer, he attained the

title "Radio Mechanic, Maximum" while in the Navy.

Escaping both the war and the 1918 Spanish Flu

pandemic with his life, he was 20 years old when he

renewed his Amateur Radio license in 1919, with his

old call

sign of 6NW. (It wasn't until November of 1919 that

it became legal once again for an amateur to own a

transmitter.)

He never mentioned whether he had (or needed) a

license while in the Navy, but all radio licenses

for Amateurs had to be reissued in 1919. Since he

was at Alameda in 1919 he probably went to San

Francisco to take the test, which is a short

distance away. (If he had been back in Los Angeles he

could have taken the written test by mail as long as

he provided an affidavit that he could send and

receive ten words per minute.) Millions of men were sent home after the

war, and by examining the dates of the known details

of his life, he had not been at the Naval base for

the whole two years of his enlistment. When he left

the navy he moved back home to his family at

Crockett Boulevard in Los Angeles.

1919 was during the age of the spark gap

transmitter. Elmer's first transmitter was a spark

plug coil from a Ford automobile that was fed with

an AC doorbell transformer. The tone changed during

transmission as the points got hot! His second

transmitter, which he called his "handsome homemade

rotary spark," was fed with a 1/2 kilowatt

transformer from Sears and Roebuck. At the first

press of the key the spark jumped to the shaft of

the motor, burning it out. One can imagine the look

on his face as the rapidly spinning motor slowly

came to a stop - permanently. Later he "got a new

rotary spark gap" and "proceeded to jam up the air."

There were only a handful of operators on the air

back then, and the best distance one could get was

about 30 miles. His self-designated call letters

were "EO" till the government made amateurs get a

license because they were having "too much fun."

His receiver was a loose coupler with an Audion

vacuum tube

detector.

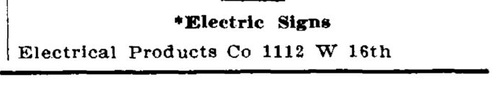

| A "Navy Type"

loose coupler from 1921. (It's a

"loose" coupler because the coil on

the right slides in and out of the

box, which houses a larger coil.

Taps on the large coil are connected

to the switches on the front.)

Elmer's loose coupler may have

resembled this one, but there is

no way we'll ever know. It is

just shown here as an example. |

NOTE: A spark gap transmitter basically transmitted

bursts of static. These bursts were created by

rapidly opening and closing the connection to the

low voltage side of an induction coil. Elmer used

the spark plug coil from a Ford, possibly a Model T.

(The coils were so plentiful that you can still buy

one today.) The tone was determined by how quickly

the circuit was interrupted, and this is probably

what Elmer's AC doorbell was used for. The rotary

spark transmitted a higher pitched tone, but it was

still just a controlled form of static.

When Elmer wrote that he "proceeded to jam up the

air" he wasn't kidding. These signals were so broad

that two transmitters operating within a short

distance of each other would drown everyone else out,

blanketing the airwaves with noise. By 1921 the

government refused to license any amateur who used a

spark gap transmitter which was directly connected

to an antenna.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

A Ford Model T ignition coil from 1914 and an

antique doorbell. Of course, they wouldn't

have been antique in 1919.

|

|

| Not all Model

T coils look exactly like this one, but they

are similar. The Ford Model T had four

coils, each one in a wooden box. Millions of

Model Ts had been produced by 1919 so there

were plenty of coils to be had. There is a

vibrator mounted on the top to create a high

voltage spark, but Elmer used the doorbell

(hopefully, minus the bell). |

The "Pacific Radio News" issue of May 10, 1920 lists

Elmer as holding the radio call letters 6NW. He is

also listed in "The Consolidated Radio Call Book"

from May, 1922 and the "Citizen's Radio Call

Book" dated November 1922, with the same call sign.

Listing in the May, 1920

issue of

"The Consolidated Radio Call Book" |

According

to "Amateur Stations of the United States," in 1920

and 1921 Elmer had a 1000 watt station at 8011

Crockett Street in Los Angeles. Elmer later wrote

that the power was actually 500 watts. The June,

1922 edition of the same publication shows that

Elmer's call letters had been reassigned to J. F.

Upchurch of Vallejo, California.

|

Osterhoudt entry in the 1920

Los Angeles City Directory. |

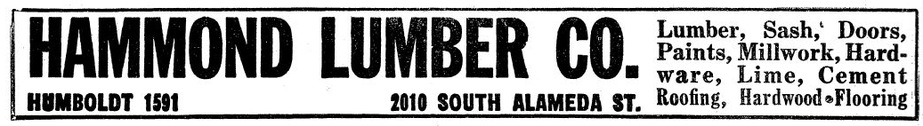

An entry in

the Los Angeles 1920 City Directory shows an E. G.

Osterhoudt working as a laborer at Hammond Lumber

Company on Alameda Street, and the 1920 census shows

William Osterhoudt working at Blinn Lumber Company

as a carpenter. Though Hammond Lumber was about four

miles from their house on Crockett Blvd, Alameda

Street was only a few blocks away. A trolley car

could have transported Elmer up Alameda Street in less

than a half an hour.

As for his roles at Majestic Electrical Products and

U. S. Motor Company, Elmer never mentioned these in

his writings, nor did he ever mention working in a

lumber or paper mill, nor did he mention how hard it

was for a veteran to find a job after the war.

Likewise, he never mentioned that in 1920 he was a

member of the California Academy of Sciences.

The January 1920 US Census shows Elmer working for a

power company in Fresno, CA as a wireless operator.

In June of 1920, he traveled to San Francisco hoping

to land a job as a radio operator aboard a ship. He

arrived on a Saturday. By Sunday he was down to his

last $20. By Monday he was employed at Southern

California Edison Company as a wireless operator.

Apparently, he wasn't there very long.

According to Elmer's application to the Society of

Wireless Pioneers, in 1920 he was at the RCA

wireless station at Marshall, California, about 40

miles north of San Francisco. Today the station is

an historic landmark in a park-like setting, but

when Elmer was there it was surrounded by barren

coast land. He was only there a week. In July of

1920 he finally obtained a wireless operator

position aboard a ship.

Elmer relates in MRL Data Sheets Vol. 6 that

in 1920, while in San Francisco and waiting to go to

sea, he had $25 and spent $20 of it on a Kodak

camera to take a picture of a Japanese ship named

"Tenyo Maru."

The Japanese

passenger liner SS Tenyo Maru docked at

San Francisco in 1920. The photo Elmer

took may have looked very much like this

one. This photograph was taken at the

Brannan Street Wharf in San Francisco on

October 5, 1920, which places Elmer at

this very spot around the same date.

Source.

Elmer may have had an interest in this

ship because it was the first turbine

driven steamship ever to enter the port

of San Francisco. It carried Asian

immigrants to Angel Island Immigration

Station, an island in San Francisco bay.

Note: In this photo the ship is docked

between piers 34 and 36. Built in 1909,

the piers have since collapsed and have

been replaced with a public park. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

This crop from the 1920

Compton Union High School Alumni page shows

Elmer as a 1918 graduate. He's working for

Standard Oil. (Watts, CA is where he lived

when he attended the school.) Notice that

Elmer Stevens, whom we believe is the

neighbor boy who brought his radio to Elmer

Osterhoudt in 1915 (see top of page), is a

plumber.

|

|

From 1920 to

1923 Elmer was at sea employed as a wireless radio

operator. On July 6, 1920 he was the operator aboard

the S. S. Rose City. This was a passenger ship named

after the city of Portland, Oregon.

On July 20, 1920 he was the radio operator on

"Standard Oil Barge 93."

On January 25, 1920 he served aboard a steam ship

named the J. A. Moffett, also owned by Standard Oil

of California. The J. A. Moffett, named after the

former president of Standard Oil of California, was

launched in 1914 and was the largest oil tanker in

the Pacific at the time. The radio call letters were

"WRE." Elmer made $225 a month,

which he said was "good money" (It was

$100 more than the average salary for a radio

operator on a ship at the time). On November 2, 1920,

during the Harding-Cox presidential election, the

ship was docked at Vancouver, British Columbia. At

the request of the captain, Elmer remained at the

radio in contact with station NPG in San Francisco.

When the election was over he gave the Captain the

results, then left the ship and "ran up and down

Hastings Street."

In 1921 there

was some sort of strike, which backfired. The radio

operators lost $20 a month, and on July 21, 1921

Elmer ended up on a lumber scow named the

"Willamette." Apparently, life aboard the

Willamette wasn't very pleasant due to the light

ship lurching in the waves. Elmer wrote that he got

six meals a day; "three down and three up." A good

part of his time was spent "hanging over the rail."

A Radio Service Bulletin dated October 1, 1921

lists a "Willamette" with a transmitter range of 200

miles. It had a Gray and Danielson radio. Gray and

Danielson, also known as Remler Company, was founded

in 1918 in San Francisco, so this seems to be the

correct ship. (Searching on the Internet for

"Willamette" will lead you down many strange paths.)

On August 31, 1921, Elmer was aboard the tug named

"Sea Lion." In a newspaper article published by the

Oregon Daily Emerald on November 29, 1921 it

states that radio operator Elmer G. Osterhoudt is

working aboard the tug "Sea Lion," plying up and

down the Pacific coast, where he is also studying

botany and physiology. (He was taking a

correspondence course from the University of Oregon

at the time, ergo the newspaper article.) By

September 28, 1921 he was working aboard the SS

Atlas, an oil tanker owned by Standard Oil of

California.

| |

|

|

| |

The

tugboat "Sea Lion," built in 1920 at the

Main Street Iron Works, San Francisco, CA. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

On September 28, 1921, Elmer was in the

radio room of the SS Atlas, owned by

Standard Oil Co. of California.

(This photo was taken at the Standard Oil

facility in Ketchikan Alaska at an unknown

date.) |

|

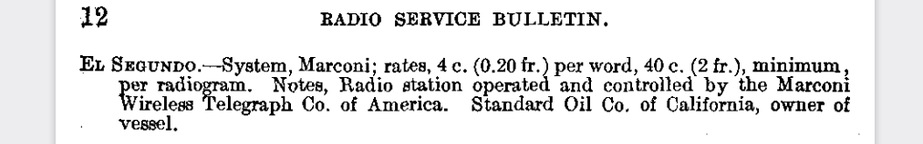

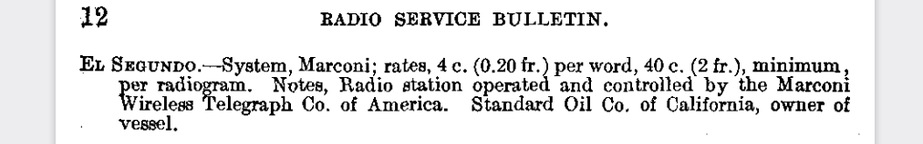

Entry from Radio Service Bulletin, US Department of

Commerce, January, 1915. Page 12.

(NOTE: Marconi Wireless was incorporated into the

Radio Corporation of America in October, 1919)

By June 17, 1922 Elmer worked aboard the F. H.

Hillman, an oil tanker built in 1921 at the Alameda

Works Shipyard, also owned by Standard Oil of

California.

From July 3, 1922 to September 4, 1923 he worked

aboard the "El Segundo," an oil tanker built in 1912

and owned by Standard Oil. Though the SS Atlas, the J. A. Moffett, the F. H.

Hillman and the El Sugundo were owned by Standard

Oil , Elmer actually worked for RCA. Elmer wrote

that in the 1920s he reported to a Chief Radio

Operator named Dick Johnson, who worked for RCA. On

the next page is a letter Elmer wrote while aboard

the ship, signed "care of Radio Corporation of

America."

Aboard ship, Elmer was known as "Sparks," a common

nickname for the radio operator. Elmer said that he

"quit" in 1923. By then, almost every other ship on

the Pacific coast was a Japanese cargo ship. Elmer

wrote, "After an OP spends several years at sea, he

gets sick of the monotony of sea life and looks for

a land station job." In a contradiction, Elmer

also wrote in Radio Operating as a Career "If

you spend a few years at sea - you'll never get off

- it is so fascinating."

In addition to the correspondence course in botany

he took from the University of Oregon, he was

enrolled in a correspondence course in Pharmacy

during his time at sea. In Elmer's own vague words,

"Read up on Pharmacy for 2 yrs. with phones on."

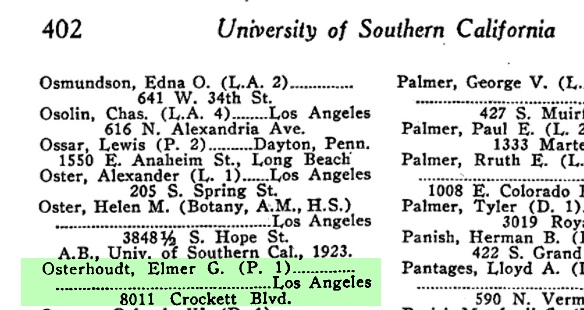

In 1923 he

attended one semester at the University of Southern California College of Pharmacy in

Los Angeles.

Afterwards, he became "official janitor"

(his own words) in a drug store, and contemplated

the idea of owning his own drug store. Elmer wrote, "I had a

lot with my 6NW on the back." which he sold for

$1000. With that and the money he saved while at sea

(he called it Ship money), he opened a store.

Thankfully, it wasn't a drug store.

"I had a lot with my 6NW on the back." -

Elmer Osterhoudt

MRL MYSTERY: Three separate publication list 6NW as

being located at 8011 Crockett Blvd. This was the

address of the Osterhoudt residence, presumably

owned by Elmer's father. How did Elmer have a "lot"

that he could sell at that address? What does "a lot

with my 6NW on the back" actually mean, and was

it worth $1000?

It's possible that in the early 1920s some of the

properties on Crocket Blvd were empty lots. Elmer

could have purchased one and built a ham shack on

the rear of the lot, ergo "6NW [was] on the back." Around 1927 the Osterhoudt's moved from 8011 to

8019 Crockett Blvd. These two properties ARE RIGHT

NEXT TO EACH OTHER. Was 8019 Elmer's lot? Did he

sell it to his father in 1924? A 1924 edition of the

Los Angeles Daily News shows that $1000 for

a lot was about right.

Is "a lot with my 6NW on the back" a figure of

speech? If it meant his radio equipment, he sold it

for the equivalent of over $18,000 in 2025 dollars. His amateur

license (6NW) which he acquired in 1917 expired in

May of 1922. He resigned

from RCA as a radio operator in 1923. Did

he build a state of the art ham radio station worth

$18,000 while also being at sea for most of those

years? Would the technology

available at the time have cost that much?

The November 1923 issue of Radio Age

reported that S. P. Stocking, whose call was 9AZH,

had his station equipment stolen. It was valued at

$1,500. Because of this report we know Elmer's

equipment alone could have been worth $1000.

"A lot with my 6NW on the back" was either his

radio station or a piece of real estate.

Whatever it was, he got $1000 for it. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |